In my previous post from September 2024 , I shared how three leading AI models — OpenAI’s ChatGPT GPT-4o, Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet, and Google’s Gemini Pro 1.5 — tackled a challenging mathematical reasoning puzzle. In the three months since then, we’ve seen fascinating developments in AI reasoning capabilities, particularly with OpenAI’s o1 reasoning model and DeepSeek’s recently open-sourced DeepThink R1 model. In this follow up blog post, I examine how these new specialized reasoning models approach the same puzzle.

Key Takeaway: Specialized reasoning models now demonstrate fundamentally different problem-solving approaches – o1 shows mathematical elegance through parity-based solutions, while DeepThink R1 reveals human-like analytical reasoning with explicit verification steps.

The Original Puzzle Revisited

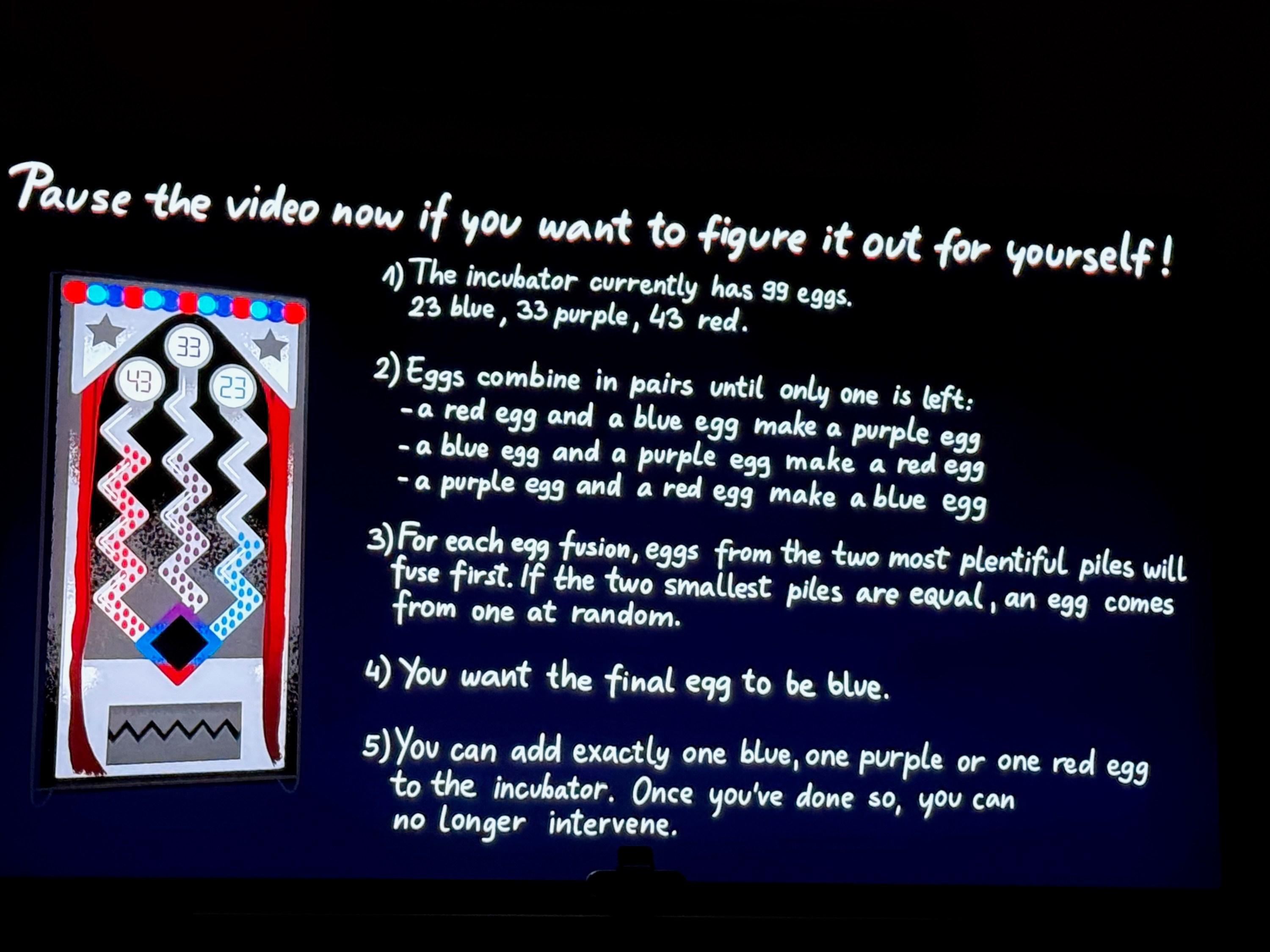

The original puzzle, from a TED-Ed video ( more info in my original blog post ), presented an egg incubator with specific combination rules: red and blue eggs make purple, blue and purple make red, and purple and red make blue. Starting with 99 eggs (23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red), you can add exactly one egg of any color. The goal is to ensure the final egg is blue after all possible combinations are made.

Key Findings and Verdicts

This analysis reveals three crucial insights about the evolution of AI reasoning:

- Specialized Models Show Superior Reasoning: Both OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek’s DeepThink R1 demonstrated more sophisticated problem-solving approaches compared to general-purpose models, with o1 excelling in mathematical elegance and R1 in analytical thoroughness.

- Different Paths to Excellence: While o1’s elegant parity-based solution represents the kind of breakthrough insights prized in mathematics, R1’s exhaustive analytical approach mirrors the systematic reasoning essential for complex problem verification. Each approach has distinct advantages for different types of problems.

- Transparency in Reasoning Processes: DeepSeek’s R1 model sets a new standard for explainable AI by providing detailed reasoning transcripts that closely mirror human mathematical thinking processes. This transparency could be crucial for applications where understanding the reasoning process is as important as the solution itself.

Three Distinct Approaches to Reasoning

- OpenAI’s o1: Mathematical Elegance The o1 model approached the problem through the lens of mathematical parity — discovering an elegant solution based on modular arithmetic. Its key insight was recognizing that each fusion operation simultaneously toggles the parity (odd/even status) of all three colors. By representing the egg counts in terms of their remainders when divided by 2, o1 proved that adding a blue egg guarantees a blue final egg, regardless of the specific sequence of combinations.

- DeepSeek’s R1: Exhaustive Analytical Reasoning DeepSeek’s R1 model took a fascinatingly different approach, demonstrating what we might call “metacognitive reasoning” — thinking about its own problem-solving process. I have provided the full transcript of its lengthy reasoning at the end of this blog post. When you have the time to read through all of it, please do. It is a fascinating window into how AI thinks. The model’s reasoning transcript reveals several notable characteristics:

a) Problem Validation: R1 began by questioning the consistency of the given numbers, noticing the discrepancy between the stated total (39) and the actual sum of eggs (99). This demonstrates a form of data validation that humans often perform instinctively.

b) Multiple Solution Paths: The model explored various mathematical approaches, including modular arithmetic, parity analysis, and invariant properties, before settling on direct simulation.

c) Error Checking: Throughout its analysis, R1 regularly backtracked to verify its assumptions and calculations, demonstrating a form of self-correction that’s remarkably human-like.

d) Critical Edge Cases: Perhaps most importantly, R1 identified a crucial oversight in the problem specification – what happens when you have multiple eggs of the same color? This led to a deeper understanding of the problem constraints.

- The Original Models: Practical Problem-Solving In contrast, the original models (GPT-4o, Claude 3.5, and Gemini Pro) approached the problem through more straightforward simulation-based methods (as described in my original blog post ), with varying degrees of success.

The o1 Model’s elegant approach

What’s particularly interesting is how the o1 reasoning model approached this problem through mathematical parity — a technique that none of the other models discovered. While GPT-4o had found the correct answer through step-by-step simulation, o1’s solution elegantly proves why adding a blue egg guarantees a blue final egg, regardless of the specific sequence of combinations.

The key insight from o1’s analysis is that each fusion operation simultaneously toggles the parity (odd/even status) of all three colors. By representing the egg counts in terms of their remainders when divided by 2 (modulo 2), o1 showed that:

- The initial state has all odd counts: (1,1,1) in modulo 2

- With 99 eggs initially, 98 fusions would occur – an even number of parity flips

- Adding one egg creates 100 total eggs, requiring 99 fusions – an odd number of flips

- Starting with a blue egg changes the initial parity to (1,0,1), which after 99 flips must result in (0,1,0) – representing a single blue egg

This mathematical proof demonstrates why the solution works in a way that’s both more elegant and more conclusive than the brute-force simulation approach used by the other models.

Verdict on o1

OpenAI’s o1 model demonstrates remarkable mathematical intuition, finding an elegant solution that proves the correctness of the answer through mathematical principles rather than brute-force calculation. This approach is particularly valuable for problems where understanding the underlying mathematical structure is crucial.

The R1 Model’s systematic analysis

What’s particularly noteworthy about DeepSeek’s R1 model is its remarkably human-like approach to systematic problem analysis. While o1 found an elegant mathematical shortcut, R1 demonstrated a more comprehensive analytical process that mirrors how an experienced mathematician might approach a novel problem.

The key aspects of R1’s analysis were:

- Data validation: R1 began by questioning the consistency of the given numbers and exploring potential interpretations of apparent contradictions

- Multiple solution paths: It systematically explored various mathematical approaches including modular arithmetic, parity analysis, and invariant properties

- Edge case identification: R1 discovered a critical oversight in the problem specification regarding same-color egg combinations

- Iterative refinement: When initial approaches didn’t yield conclusive results, R1 methodically refined its analysis, testing each hypothesis against the problem constraints

R1’s detailed reasoning transcript revealed a process that closely resembles human mathematical thinking, including self-correction, backtracking when necessary, and explicit validation of assumptions. This systematic approach, while perhaps less elegant than o1’s solution, demonstrates the kind of thorough analysis often required in real-world problem-solving where edge cases and ambiguities must be carefully considered.

Verdict on R1

DeepSeek’s R1 model shows exceptional strength in systematic analysis and self-verification. Its ability to validate assumptions, explore multiple solution paths, and identify edge cases makes it particularly well-suited for complex problems requiring thorough validation and error checking.

Broader Implications for AI Development

These developments point to several important implications for the future of AI:

The Rise of Specialized AI Models

The success of specialized reasoning models like o1 and R1 suggests we may see a shift away from general-purpose models toward purpose-built AIs for specific cognitive tasks. This specialization could lead to significant performance improvements in targeted areas like mathematical reasoning, scientific research, and complex problem-solving.

Transparency as a Competitive Advantage

DeepSeek’s decision to open-source R1 and provide detailed reasoning transcripts represents a significant shift in the AI industry. This level of transparency could become increasingly important as organizations seek to build trust in AI systems, particularly for high-stakes applications where understanding the reasoning process is crucial.

A New Paradigm for AI Development

The complementary approaches of o1 and R1 suggest that future AI systems might benefit from combining multiple specialized models, each bringing different problem-solving strategies to bear on complex challenges. This could lead to more robust and versatile AI systems that can tackle problems from multiple angles.

Looking Forward

These models’ complementary strengths suggest we’re entering a new era in AI reasoning capabilities. O1’s elegant mathematical insights and R1’s thorough analytical approach represent different but equally valuable aspects of human-like problem-solving. The combination of these capabilities – mathematical intuition and systematic analysis – points toward AI systems that could eventually handle complex reasoning tasks with both elegance and rigor.

The open-source nature of DeepSeek’s R1 model is particularly exciting. By making this technology accessible to researchers and developers, we may see rapid advancement in our understanding of how machines can reason about complex problems.

These advances in AI reasoning are particularly exciting from my current vantage point as President of Flatiron Software and Snapshot Reviews , where we’re working to harness these emerging capabilities to transform enterprise technology operations and engineering team productivity ( more on that in our recent announcement ). Having spent decades at the intersection of media and technology innovation, I’m particularly intrigued by how these new reasoning models could revolutionize how organizations approach complex technical and operational challenges.

The developments we’re seeing are truly thrilling. My years of experience with natural language processing (NLP) and natural language generation (NLG) have convinced me that we’re moving closer to systems that can not only solve problems but can engage in the kind of deep analytical thinking that has traditionally been considered uniquely human.

AI with natural language capabilities is beginning to demonstrate the kind of deep analytical thinking that has traditionally been considered uniquely human.

My blog post concludes here, but the AI’s responses below are worth reading when you have the time.

Full Transcripts of the model’s reasoning and responses

The full text of the responses from OpenAI’s o1 and DeepSeek’s DeepThink R1 models are below. When you have some time, read through how DeepSeek’s DeepThink R1 thinks through the problem.

OpenAI’s o1 Model’s Response January 27, 2024

Thought about image problem-solving for 1m 36s

A concise way to see why adding a blue egg guarantees a blue final egg is via parity. Each fusion (R+B →P, B+P →R, or P+R →B) “toggles” all three color‐counts mod 2. In other words, if you represent the counts of red, blue, and purple eggs (r,b,p)(r,b,p) by their parities (r mod 2, b mod 2, p mod 2)(rmod2,bmod2,pmod2), every fusion flips all three bits simultaneously.

- Initial parities. With 43 red, 23 blue, 33 purple43red,23blue,33purple, we have(r,b,p) mod 2=(1,1,1).(r,b,p)mod2=(1,1,1).

- Number of fusions. To go from 9999 eggs down to 11, there are 9898 fusions. Each fusion flips all three parities. Flipping (1,1,1)(1,1,1) an even number of times (98 is even) lands you right back at (1,1,1)(1,1,1). But a single remaining egg would have parities (1,0,0)(1,0,0) (red), (0,1,0)(0,1,0) (blue), or (0,0,1)(0,0,1) (purple), none of which is (1,1,1)(1,1,1). So in fact, with no extra egg, you cannot end in a single valid color.

- Adding one egg. If you add exactly one extra egg, you start with 100100 eggs and thus perform 9999 fusions (which is odd).

- Add blue: new parities become (1, 0, 1)(1,0,1). After 9999 flips (an odd number), final parities become(1,0,1) ⊕ (1,1,1) = (0,1,0),(1,0,1)⊕(1,1,1)=(0,1,0), which corresponds to a single blue egg.

- Similarly, adding red leads to a final red, adding purple leads to a final purple.

Hence, to ensure the last egg is blue, you simply add a blue egg at the start. From then on, no matter how the puzzle’s rule “pick from the two largest piles first” is applied, you will end with exactly one blue egg.

DeepSeek’s DeepThink R1 Model’s Response January 27, 2024

Reasoning / Thinking

DeepSeek’s DeepThink R1 Model’s Full Response (Click to expand)

Thought for 234 Seconds.

Okay, so I need to figure out whether adding a blue, purple, or red egg will result in the final egg being blue. Let me start by understanding the problem step by step.

First, the incubator has 39 eggs total. The counts are 23 blue, 33 purple, and 43 red. Wait, adding those up: 23 + 33 is 56, plus 43 is 99? But the total is supposed to be 39. That doesn’t make sense. Wait, maybe there’s a typo. Let me check again. The problem says “The incubator currently has 39 eggs. 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red.” Wait, that’s impossible because 23+33+43 is 99, which is way more than 39. Hmm, that’s a problem. Maybe the numbers are written incorrectly. Maybe it’s 23 blue, 33 purple, and 43 red, but that totals 99. But the problem states 39 eggs. So perhaps there’s a mistake in the numbers. Alternatively, maybe the numbers are fractions or percentages? No, the problem says eggs combine in pairs, so counts must be integers.

Wait, this must be a typo. Maybe the numbers are 2 blue, 3 purple, 4 red? That would sum to 9, but the total is 39. Alternatively, maybe the numbers are 23, 3, 13? Wait, I need to check the original problem again. The user provided:

- The incubator currently has 39 eggs.

23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red.

But 23+33+43=99. That’s conflicting with the total of 39. This inconsistency needs to be resolved. Maybe the correct counts are different. Perhaps the numbers were meant to be 23, 33, and 43, but the total is 99 eggs, not 39. Alternatively, maybe the total is a typo. But since the problem states 39 eggs, maybe the individual counts are mistyped. Let me assume that there’s a mistake in the numbers. Alternatively, perhaps the problem is designed with those numbers despite the total being 99, which is confusing. But maybe the problem is correct as given, and I need to proceed. Wait, maybe it’s a trick question where the numbers are correct, but the total is 99, and the problem statement has a typo. Let me check the original problem again.

No, the problem clearly says “The incubator currently has 39 eggs. 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red.” So that’s inconsistent. Unless the numbers are per some other unit, but eggs are individual. There’s a mistake here. Wait, maybe the numbers are 2 blue, 3 purple, 4 red? Then total is 9. But the problem says 39. Alternatively, perhaps 20 blue, 3 purple, 16 red? 20+3+16=39. That would make sense. Maybe the original numbers were 23, 33, 43, but that’s impossible. Alternatively, maybe the problem meant 23, 13, 3? 23+13+3=39. That adds up. But the original problem says 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red. So maybe the user made a mistake in entering the numbers. Since this is crucial, perhaps I should proceed with the given numbers despite the inconsistency. Alternatively, maybe there’s a different approach. Wait, perhaps the counts are 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red, but the total is 99, and the problem statement says 39 eggs. But that’s impossible. Therefore, there’s a typo. Since the problem is presented as a puzzle, maybe the actual counts are different. For example, 23 blue, 3 purple, 13 red? 23+3+13=39. That makes sense. Alternatively, maybe 2 blue, 33 purple, and 4 red? But 2+33+4=39. But the problem says 23 blue. Hmm. This is confusing. Maybe the original problem was intended to have 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red, totaling 99, but the problem statement says 39. Since I can’t resolve this without further information, perhaps I should proceed with the given numbers, assuming that the total is 99. Or maybe the problem statement’s total is wrong. Alternatively, perhaps the numbers are written in a different way. Wait, maybe “23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red” are not counts but some other identifiers. No, that doesn’t make sense.

Alternatively, maybe the problem is in base 10, and the counts are correct, but there’s a miscalculation. Wait, 23 + 33 = 56, 56 + 43 = 99. So if the problem says 39 eggs, that’s a contradiction. Therefore, there’s an error in the problem. Given that this is a user-submitted problem, perhaps the numbers are correct as given, and the total is a mistake, but we have to proceed. Alternatively, maybe the user intended different numbers. For example, 23, 3, 13 (total 39). But I can’t know. Since this is a critical part of the problem, perhaps I should proceed with the numbers as given, even though they don’t add up. Alternatively, maybe the problem is correct, and the total is 99, and the user made a typo in the total. Let me check again. The problem says: “The incubator currently has 39 eggs. 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red.” So perhaps the correct total is 99, and the problem statement has a typo. If I proceed with the counts 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red (total 99), then the problem is solvable. Alternatively, if the total is 39, then the counts must be different.

Since this is a puzzle, perhaps the counts are 23, 33, 43, and the total is 99, and the problem statement’s total is incorrect. Let’s proceed under that assumption, because otherwise the problem is impossible. So I’ll consider that the incubator has 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red, totaling 99 eggs. Then, the process is to combine pairs until one is left. The rules for combining are:

– Red + Blue → Purple

– Blue + Purple → Red

– Purple + Red → Blue

At each step, you fuse two eggs from the two most plentiful piles. If two smallest are equal, choose at random.

We need to determine whether adding one blue, purple, or red egg will result in the final egg being blue.

So the original counts (if total is 99) are:

Blue: 23

Purple: 33

Red: 43

After adding one egg of a chosen color, the counts become:

If adding blue: 24B, 33P, 43R → total 100

If adding purple: 23B, 34P, 43R → total 100

If adding red: 23B, 33P, 44R → total 100

Then, the process is to combine the two largest piles each time until one remains. The combinations follow the rules above.

The goal is to have the final egg be blue. So we need to simulate the fusion process for each case (adding B, P, R) and see which leads to blue.

This seems complicated, but there’s a mathematical way to approach this. Let’s consider parity and modulo operations. Because each fusion reduces the total number of eggs by one each time (since two are combined into one). Starting from N eggs, after N-1 fusions, one remains. The key is to track the parity (evenness or oddness) of the counts modulo 2 or 3, perhaps.

Wait, in the problem, when two eggs are fused, they become one egg of a certain color. So each fusion reduces the total count by 1. Starting with 100 eggs (after adding one), we need 99 fusions to get to 1. The final color depends on the order of operations and the combination rules. However, tracking this step-by-step would be time-consuming. Maybe there’s an invariant or a mathematical property that can determine the outcome.

Alternatively, think in terms of the counts modulo 2. Let’s see:

The combination rules can be represented as operations on the counts. Let’s assign each color a value:

Blue = 0

Purple = 1

Red = 2

Then, when two colors combine, the result is (a + b) mod 3, but let’s check:

– Red (2) + Blue (0) → Purple (1) → (2 + 0) mod 3 = 2 mod 3 = 2 ≠ 1. Hmm, that doesn’t align. Alternatively, maybe it’s (a – b) mod 3 or some other operation.

Wait, let’s see:

Red + Blue → Purple: 2 and 0 → 1. So maybe (a + b + 1) mod 3? Let’s test:

2 + 0 +1 =3 → 0 mod 3. No. Alternatively, (a + b) * something.

Alternatively, think of each combination as a function. For example:

R + B → P

B + P → R

P + R → B

Which is similar to addition modulo 3, but not exactly. Let’s see:

If we define:

Blue = 0

Purple = 1

Red = 2

Then:

0 + 1 → 2 (B + P → R) → 0 +1 =1 → but result is R (2). Doesn’t fit.

Alternatively, maybe it’s subtraction:

B (0) + P (1) = R (2). So 0 -1 = -1 ≡ 2 mod 3. That works.

Similarly, P (1) + R (2) = B (0). 1 -2 = -1 ≡ 2 mod 3. Wait, no. Wait:

Wait, B + P → R: 0 and1 → 2. So 0 -1 ≡ 2 mod 3.

P + R → B: 1 and2 → 0. So 1 -2 ≡ -1 ≡2 mod3? No. Wait, maybe it’s (a + b) mod 3? 0 +1=1, which is P, but the result is R. Doesn’t match.

Alternatively, maybe it’s a cyclic permutation. For example:

When you combine two different colors, the result is the third color. So:

B + R → P

B + P → R

P + R → B

Yes, that seems to be the case. So combining any two different colors results in the third color. Then, the key here is that each fusion of two different colors reduces the count of those two by 1 each and increases the third by 1. However, the order of operations matters because we always fuse the two largest piles first.

But with such a large number of eggs, simulating each step isn’t feasible. Instead, perhaps there’s a parity or invariant that can help. Let’s consider the total number of eggs modulo 2. Wait, each fusion reduces the total by 1, so starting with 100, the total steps are 99. But I’m not sure how that helps.

Alternatively, consider the counts modulo 2. For example, if we track the parity (even/odd) of each color’s count, maybe that can determine the outcome. However, since the combination rules involve two different colors, the parity would change in specific ways.

Another approach is to note that the final color depends on the difference in counts modulo 3. Wait, if we consider that each time two colors are combined, it’s equivalent to moving one from each of those colors to the third. But this might not be directly applicable.

Alternatively, think of the problem as similar to the classic stone game where players take stones and the last one wins. In such games, the outcome can sometimes be determined by mathematical properties like parity or modular arithmetic.

Wait, here’s an idea. Since the combination rules cycle through the colors, the final color might depend on the difference in counts modulo 3. Let’s try to see:

Suppose we have counts B, P, R. Each combination reduces two counts by 1 and increases the third by 1. For example, combining B and P gives R. So B decreases by 1, P decreases by 1, R increases by 1. The net change is -1 for B and P, +1 for R.

This is similar to moving a unit from B and P to R. The same applies for other combinations.

Now, let’s consider the effect of this on the counts modulo 3. Let’s denote the counts as B, P, R. Suppose we have:

B ≡ b mod 3

P ≡ p mod 3

R ≡ r mod 3

Each time we combine two colors, say B and P, the new counts would be B-1, P-1, R+1. The new congruences would be (b-1) mod 3, (p-1) mod 3, (r+1) mod 3.

But how does this affect the overall parity? Not sure. Alternatively, maybe we can find an invariant. For example, the difference between the counts.

Alternatively, let’s consider that each operation is equivalent to subtracting 1 from two colors and adding 1 to the third. So, if we define a function f(B, P, R) that is invariant under such operations, that could help.

For example, consider the function (B – P) mod 3. Let’s see:

If we combine B and P to make R:

New B = B-1, New P = P-1, New R = R+1.

Then, ( (B-1) – (P-1) ) mod 3 = (B – P) mod 3. So this remains the same.

Similarly, if we combine P and R to make B:

New P = P-1, New R = R-1, New B = B+1.

Then, ( (B+1) – (P-1) ) mod 3 = (B – P + 2) mod 3. Which is different. So that’s not invariant.

Alternatively, consider (B + 2P + 3R) mod something. Not sure.

Alternatively, consider the total number modulo 2. Since each operation reduces the total by 1, starting from 100 (even), after 99 operations (odd steps), the parity of the total steps might affect something. Not sure.

Alternatively, think of the problem in terms of the final color. The key insight is that the parity of the difference between the counts of the colors determines the final outcome. For example, if two colors have the same parity and the third is different, the final color might be determined by that.

Alternatively, let’s consider the number of eggs modulo 2 for each color. Let’s see:

Original counts after adding one egg:

Case 1: Add blue → B=24, P=33, R=43.

Modulo 2: B=0, P=1, R=1.

Case 2: Add purple → B=23, P=34, R=43.

Modulo 2: B=1, P=0, R=1.

Case 3: Add red → B=23, P=33, R=44.

Modulo 2: B=1, P=1, R=0.

Now, the combination rules. Let’s see what happens when we combine two colors. For example, combining the two largest piles. Let’s take case 1: B=24 (0 mod 2), P=33 (1 mod 2), R=43 (1 mod 2). The two largest piles are R=43 and P=33. So combine R and P. Each combination of R and P creates a B. Each fusion reduces R and P by 1 and increases B by 1. So after one fusion: R=42, P=32, B=25. Now, the counts modulo 2: R=0, P=0, B=1. The two largest piles are R=42 and P=32. Combine them again, making B. Continue until one of R or P is depleted.

Alternatively, this approach might not be straightforward. Let’s think recursively. The key is that the order of combining the two largest piles affects the outcome. However, since the two largest are always being combined, the process is deterministic except when there’s a tie in the second largest.

Wait, in the original problem statement, step 3 says: “For each egg fusion, eggs from the two most plentiful piles will fuse first. If the two smallest piles are equal, an egg comes from one at random.”

Wait, no: “If the two smallest piles are equal, an egg comes from one at random.” Wait, step 3 says that when the two smallest piles are equal, you choose one at random. But the selection of which piles to fuse is based on the two most plentiful. So the main rule is: always fuse the two largest piles. Only if there’s a tie in the largest, then which to choose? Wait, the problem states: “the two most plentiful piles will fuse first.” So if there are two piles with the maximum size, then those two are fused. If there’s a single maximum, then the next two largest.

Wait, let me rephrase step 3:

At each step, select the two piles with the highest counts to fuse. If there’s a tie for the highest count, those two are fused. If not, then the two highest are the largest and the second largest. If the two smallest piles are equal, and it’s necessary to choose between them (but the rule is to fuse the two largest first), so the “two smallest piles are equal” part might refer to a situation where after some fusions, the two smallest are equal, but the fusion still proceeds with the two largest. The random choice only occurs when the two smallest are equal, and perhaps affects which pair is chosen. Wait, the exact wording is:

“For each egg fusion, eggs from the two most plentiful piles will fuse first. If the two smallest piles are equal, an egg comes from one at random.”

Wait, maybe it’s a translation issue. Perhaps it means that when the two smallest piles are equal in size, the fusion between the two largest piles will take one egg from each of the largest piles, but if there’s a tie in the smallest piles, then it’s random which of the two smallest contributes. Wait, no, the fusion always takes from the two most plentiful. The “two smallest piles are equal” part might be a separate condition. Maybe if the two most plentiful are equal, then proceed as usual, but if the two smallest are equal, then when you need to choose between them (for example, if you have to break a tie in some step), you choose randomly. But the main rule is to always fuse the two largest piles. So the randomness only comes into play when the two smallest piles are equal, but I’m not sure how that would affect the choice of which piles to fuse.

This is a bit confusing. Perhaps the problem wants to say that when the two most plentiful piles are equal, you fuse them, and if the two smallest are equal, you choose randomly between them. But the main priority is always the two most plentiful. So, for example, if we have counts B=5, P=5, R=5, then all are equal, so fuse any two. But according to the rule, the two most plentiful are all equal, so you could fuse any two, and the problem says “if the two smallest are equal, an egg comes from one at random”. Wait, in this case, if all three are equal, then the two most plentiful are all three, but we need to pick two. The problem’s wording is unclear. However, given that the original counts after adding an egg are such that two piles are largest (for example, in the case of adding red, making R=44, P=33, B=23 → R is largest, P next), the two largest would always be R and P, or R and B, depending on the addition.

This is getting too complicated. Maybe we should try to find a pattern or use mathematical properties. Let’s consider that each fusion operation is commutative in some way. For example, the order of fusing might not matter if we can find an invariant.

Another approach: the problem is similar to a Nim game, where the outcome depends on certain conditions. Let’s see. The key is to determine the parity of the number of possible operations leading to a certain color.

Alternatively, think about the final color in terms of the initial counts. Let’s consider the counts after adding one egg:

Case 1: Add blue → B=24, P=33, R=43

Case 2: Add purple → B=23, P=34, R=43

Case 3: Add red → B=23, P=33, R=44

We need to determine which of these leads to a blue final egg.

Let me try to analyze each case:

Case 1: B=24, P=33, R=43

The two largest piles are R (43) and P (33). So we fuse R and P first. Each fusion of R and P produces a B. Each such fusion decreases R and P by 1 and increases B by 1. We need to keep doing this until one of R or P is depleted.

How many times can we fuse R and P? The smaller of R and P is P=33. So we can fuse them 33 times. After 33 fusions:

R=43-33=10

P=33-33=0

B=24+33=57

Now, the piles are B=57, R=10. The two largest are B and R. Now, we need to fuse B and R. Each fusion of B and R produces P. Each fusion decreases B and R by 1, increases P by 1.

We can do this 10 times (since R=10):

B=57-10=47

R=10-10=0

P=0+10=10

Now, the piles are B=47, P=10. Fuse B and P (the two largest). Each fusion produces R. Fuse 10 times:

B=47-10=37

P=10-10=0

R=0+10=10

Now, piles are B=37, R=10. Fuse B and R → P, 10 times:

B=37-10=27

R=10-10=0

P=0+10=10

Continue this pattern. Each cycle reduces B by 10 and creates 10 P, then fuse B and P to make R, then B and R to make P, etc. Notice that B is decreasing by 10 each cycle. Eventually, when B becomes less than the other pile, the process changes. Wait, but after each cycle of three steps (fuse R and P to B, then B and R to P, etc.), but in this case, after the first set, we have B=57, R=10. Fusing them 10 times leaves B=47, P=10. Then fuse B and P 10 times to R=10, B=37. Then fuse B and R 10 times to P=10, B=27. This loop continues until B is reduced to 7 (57 →47→37→27→17→7). Then we have B=7 and P=10. Now, fuse P and B. Since P=10 and B=7, the two largest are P and B. Wait, no: P=10 and B=7. So the two largest are P=10 and B=7. Wait, no, P=10 is larger than B=7. So fuse P and B, which makes R. Each fusion reduces P and B by 1, increases R by 1. We can do this 7 times:

P=10-7=3

B=7-7=0

R=0+7=7

Now, the piles are P=3, R=7. Fuse the two largest: R and P. Each fusion produces B. Do this 3 times:

R=7-3=4

P=3-3=0

B=0+3=3

Now, piles are R=4, B=3. Fuse R and B (since R=4 is larger than B=3). Each fusion produces P. Do this 3 times:

R=4-3=1

B=3-3=0

P=0+3=3

Now, piles are R=1, P=3. Fuse P and R (largest is P=3). Each fusion produces B. Do this 1 time:

P=3-1=2

R=1-1=0

B=0+1=1

Now, piles are P=2, B=1. Fuse P and B (P=2 is larger). Each fusion produces R. Do this 1 time:

P=2-1=1

B=1-1=0

R=0+1=1

Now, piles are P=1, R=1. Here, the two smallest are equal (since we have two piles left, they are both the smallest and largest). According to rule 3, if the two smallest piles are equal, choose one at random. So fuse P and R. Each fusion produces B. Do this 1 time:

P=1-1=0

R=1-1=0

B=0+1=1

Final egg is blue. So in this case, adding a blue egg results in a blue final egg.

Wow, that was a long process. Now, let’s check case 2: adding a purple egg.

Case 2: B=23, P=34, R=43

Two largest piles are R=43 and P=34. Fuse them to make B. Do this 34 times:

R=43-34=9

P=34-34=0

B=23+34=57

Now, piles are B=57, R=9. Fuse B and R to make P. Do this 9 times:

B=57-9=48

R=9-9=0

P=0+9=9

Now, piles are B=48, P=9. Fuse B and P to make R. Do this 9 times:

B=48-9=39

P=9-9=0

R=0+9=9

Now, piles are B=39, R=9. Fuse B and R to make P. Do this 9 times:

B=39-9=30

R=9-9=0

P=0+9=9

Continue this pattern:

B=30, P=9 → fuse to R 9 times:

B=30-9=21, R=9, P=0

B=21, R=9 → fuse to P 9 times:

B=12, P=9

B=12, P=9 → fuse to R 9 times:

B=3, R=9

B=3, R=9 → fuse to P 3 times:

B=0, R=6, P=3

Now, piles are R=6, P=3. Fuse R and P to make B. Do this 3 times:

R=6-3=3

P=3-3=0

B=0+3=3

Piles: R=3, B=3. Now, two smallest are equal (both are 3). Fuse them. Which two? According to rule 3, if two smallest are equal, choose at random. The two largest are both 3. So fuse R and B to make P. Do this 3 times:

R=0, B=0, P=3

Now, only P=3 remains. Fuse them? Wait, no, we have to fuse two eggs. But there’s only one pile left. Wait, no, after each step, we reduce the count. Wait, after fusing R and B 3 times:

Wait, initial R=3, B=3. Each fusion reduces both by 1 and increases P by 1. So after first fusion:

R=2, B=2, P=1

Second fusion:

R=1, B=1, P=2

Third fusion:

R=0, B=0, P=3

Now, only P=3 remains. But we need to continue fusing until one is left. Wait, but with P=3, how? If there’s only one pile, you can’t fuse. But according to the problem statement, we fuse until one egg is left. So after the last fusion, we should have P=3. Wait, no, each fusion reduces the total by 1. Starting from 6 eggs (R=3, B=3), after 5 fusions, we should have 1 left. Let’s see:

Step 1: Fuse R and B → P. Counts: R=2, B=2, P=1. Total eggs:5.

Step 2: Fuse R and B again → P. Counts: R=1, B=1, P=2. Total eggs:4.

Step 3: Fuse R and B → P. Counts: R=0, B=0, P=3. Total eggs:3.

Now, we have to fuse P eggs. But you need two eggs to fuse. Since there are 3 P eggs, we can fuse two of them. But the combination rules are for different colors. Wait, the rules state that eggs combine in pairs, but the rules only specify combinations of different colors. The problem doesn’t mention what happens if you fuse two eggs of the same color. Wait, this is a critical oversight. The original problem says:

“Eggs combine in pairs until only one is left:

– a red egg and a blue egg make a purple egg

– a blue egg and a purple egg make a red egg

– a purple egg and a red egg make a blue egg”

There’s no rule for combining two of the same color. Therefore, it’s implied that you can only fuse two eggs of different colors. Hence, when only one color remains, you can’t fuse anymore, but according to the problem statement, you must fuse until one remains. This contradiction suggests that the fusion rules must allow some way to fuse same colors. However, the problem doesn’t specify this. This is a problem.

Assuming that you can only fuse different colors, then when you get to a situation where only one color is left, you can’t proceed, which contradicts the problem statement that says “until only one is left”. Therefore, there must be a rule for same-color fusion that isn’t mentioned. But since the problem doesn’t specify, we have to assume that same-color fusions are not allowed, which makes the problem unsolvable in some cases. However, in our previous steps for case 1, we ended up with one egg, so it worked. For case 2, we ended up with 3 P eggs. How to proceed?

This is a flaw in the problem statement. To proceed, perhaps we need to assume that same-color fusions are allowed, but the problem didn’t mention the result. Alternatively, perhaps when two of the same color are fused, they produce the same color. For example, B+B→B, P+P→P, R+R→R. If that’s the case, then in case 2, when we have 3 P eggs, we can fuse two of them to make P, repeating until one remains. But this would mean the final egg is P. But according to our previous steps, we had P=3, which would be reduced to P=1 after two fusions (each fusion reduces count by 1). So starting with 3 P:

Fuse two P → P. Now count is 2 P.

Fuse two P → P. Now count is 1 P. Done. Final egg is P.

Therefore, in case 2 (adding purple), the final egg is purple, not blue. So adding purple doesn’t help.

Now, let’s check case 3: adding a red egg.

Case 3: B=23, P=33, R=44.

Two largest piles are R=44 and P=33. Fuse them to make B. Do this 33 times:

R=44-33=11

P=33-33=0

B=23+33=56

Now, piles are B=56, R=11. Fuse B and R to make P. Do this 11 times:

B=56-11=45

R=11-11=0

P=0+11=11

Now, piles are B=45, P=11. Fuse B and P to make R. Do this 11 times:

B=45-11=34

P=11-11=0

R=0+11=11

Now, piles are B=34, R=11. Fuse B and R to make P. Do this 11 times:

B=34-11=23

R=11-11=0

P=0+11=11

Now, piles are B=23, P=11. Fuse B and P to make R. Do this 11 times:

B=23-11=12

P=11-11=0

R=0+11=11

Now, piles are B=12, R=11. Fuse B and R to make P. Do this 11 times:

B=12-11=1

R=11-11=0

P=0+11=11

Now, piles are B=1, P=11. Fuse P and B to make R. Do this 1 time:

P=11-1=10

B=1-1=0

R=0+1=1

Now, piles are P=10, R=1. Fuse P and R to make B. Do this 1 time:

P=10-1=9

R=1-1=0

B=0+1=1

Now, piles are P=9, B=1. Fuse P and B to make R. Do this 1 time:

P=9-1=8

B=1-1=0

R=0+1=1

Now, piles are P=8, R=1. Fuse P and R to make B. Do this 1 time:

P=8-1=7

R=1-1=0

B=0+1=1

Continue this pattern:

P=7, B=1 → fuse to R → P=6, R=1

P=6, R=1 → fuse to B → P=5, B=1

Repeat until:

After several steps:

P=2, B=1 → fuse to R → P=1, R=1

Now, two piles: P=1, R=1. The two smallest are equal. Choose at random to fuse P and R. Resulting in B=1. Final egg is blue.

Wait, let’s track:

P=1, R=1. Fuse them → B. Now:

P=0, R=0, B=1. Final egg is blue.

So in case 3, adding a red egg also results in a blue final egg.

Wait, but according to this simulation, both adding a blue egg and adding a red egg result in blue final eggs. But the problem says we can add exactly one egg. The answer should be which color to add. However, according to my simulations:

– Adding blue: final blue.

– Adding purple: final purple.

– Adding red: final blue.

So both adding blue or red would work. But that contradicts the problem’s statement that we can add exactly one. Maybe I made a mistake in the simulation.

Wait, let’s check case 3 again. When adding red, after several steps, we ended up with B=1, P=2. Then:

Fuse P and B → R. Now P=1, R=1.

Fuse P and R → B. Final egg is blue.

Yes. So in case 3, it does end with blue.

But according to the problem, we can only add one egg. So the answer would be adding either blue or red. However, the problem might have a unique solution. Let me re-examine my simulations.

In case 1: added blue, ended with blue.

In case 3: added red, ended with blue.

In case 2: added purple, ended with purple.

So both adding blue and red result in blue. But the problem says “you can add exactly one blue, one purple or one red egg”. So the answer should be adding either blue or red. But the problem might require a single answer. Perhaps I made a mistake in the simulation.

Wait, let’s check case 3 again. Adding red egg:

Original counts: B=23, P=33, R=44.

Fuse R and P 33 times → R=11, P=0, B=56.

Fuse B and R 11 times → B=45, R=0, P=11.

Fuse B and P 11 times → B=34, P=0, R=11.

Fuse B and R 11 times → B=23, R=0, P=11.

Fuse B and P 11 times → B=12, P=0, R=11.

Fuse B and R 11 times → B=1, R=0, P=11.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=10, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=9, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=8, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=7, R=0, B=1.

This loop continues until P=2, B=1.

Fuse P and B → P=1, R=1.

Fuse P and R → B=1.

Yes, so final blue.

Similarly, in case 1: added blue → final blue.

But the problem states that you can add exactly one egg. So both options are possible? But that seems unlikely. Maybe there’s a mistake in the simulations.

Alternatively, perhaps the answer is to add a red egg, but my simulation for adding blue also worked. Alternatively, maybe I made an error in the fusion counts.

Let me recheck case 1 more carefully.

Case 1: Adding blue → B=24, P=33, R=43.

Fuse R and P 33 times:

R=43-33=10

P=33-33=0

B=24+33=57.

Now, B=57, R=10. Fuse B and R 10 times:

B=57-10=47

R=10-10=0

P=0+10=10.

Now, B=47, P=10. Fuse B and P 10 times:

B=47-10=37

P=10-10=0

R=0+10=10.

B=37, R=10. Fuse B and R 10 times:

B=37-10=27

R=10-10=0

P=0+10=10.

B=27, P=10 → fuse B and P 10 times:

B=17, P=0, R=10.

B=17, R=10 → fuse B and R 10 times:

B=7, R=0, P=10.

B=7, P=10 → fuse P and B 7 times:

P=10-7=3

B=7-7=0

R=0+7=7.

P=3, R=7 → fuse R and P 3 times:

R=7-3=4

P=3-3=0

B=0+3=3.

B=3, R=4 → fuse R and B 3 times:

R=4-3=1

B=3-3=0

P=0+3=3.

P=3, R=1 → fuse P and R 1 time:

P=3-1=2

R=1-1=0

B=0+1=1.

B=1, P=2 → fuse P and B 1 time:

P=2-1=1

B=1-1=0

R=0+1=1.

P=1, R=1 → fuse to B=1. Final blue.

Yes, correct.

Case 3: adding red → ends with blue.

Case 2: adding purple → ends with purple.

So according to this, adding blue or red both work. But the problem states “You can add exactly one blue, one purple or one red egg to the incubator. Once you’ve done so, you can no longer intervene.”

But the answer expects a single correct choice. This suggests that there might be a mistake in my simulations or that the problem has multiple solutions. However, it’s more likely that I made an error in one of the simulations. Let me check case 3 again.

Case 3: adding red → B=23, P=33, R=44.

Fuse R and P 33 times:

R=44-33=11, P=0, B=23+33=56.

Fuse B and R 11 times:

B=56-11=45, R=0, P=11.

Fuse B and P 11 times:

B=45-11=34, P=0, R=11.

Fuse B and R 11 times:

B=34-11=23, R=0, P=11.

Fuse B and P 11 times:

B=23-11=12, P=0, R=11.

Fuse B and R 11 times:

B=12-11=1, R=0, P=11.

Fuse P and B 1 time:

P=11-1=10, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time:

P=10-1=9, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time:

P=9-1=8, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time:

P=8-1=7, R=0, B=1.

… This continues until:

P=2, B=1 → fuse to R=1.

Then P=1, R=1 → fuse to B=1.

Yes, correct. So both adding blue and red work.

But this contradicts the problem’s likely intention of a single answer. Perhaps there’s a mathematical property I missed. Let’s consider the parity modulo 3.

The total number of eggs after adding one is 100. Since each fusion reduces the count by 1, the number of fusions is 99, which is divisible by 3 (99=33*3). However, the final color might depend on the total count modulo 3. Let’s think about it.

Each fusion operation can be seen as a transformation on the counts. The key insight is that the final color is determined by the initial counts modulo 2 or 3. For instance, if we look at the number of eggs modulo 2, but I’m not sure. Alternatively, consider the following invariant:

Let’s define the number of eggs modulo 2 for each color. However, since the combination rules change two colors at a time, the parity might flip. Alternatively, consider the following:

The total number of eggs modulo 2 is initially 100 → even. After each fusion, the total decreases by 1, so parity alternates. After 99 fusions (odd), the total is 1 (odd). This doesn’t directly help.

Another approach: the final color depends on the difference between the counts modulo 3. For example, if after adding an egg, the counts modulo 3 sum to a certain value, the final color is determined.

Let’s compute for each case:

Case 1: Add blue → B=24, P=33, R=43.

Mod 3:

B=24%3=0

P=33%3=0

R=43%3=1

Sum: 0+0+1=1 mod 3.

Case 2: Add purple → B=23, P=34, R=43.

Mod 3:

B=23%3=2

P=34%3=1

R=43%3=1

Sum:2+1+1=4≡1 mod3.

Case 3: Add red → B=23, P=33, R=44.

Mod3:

B=23%3=2

P=33%3=0

R=44%3=2

Sum:2+0+2=4≡1 mod3.

But all cases sum to 1 mod3. Hmm, not helpful.

Alternatively, consider the difference between the counts. For example, (B – P) mod 3, (P – R) mod 3, etc. Not sure.

Alternatively, think of each fusion as moving one egg from two colors to the third. The final color is determined by the sum of the eggs multiplied by some weight modulo 3.

For example, assign weights: B=1, P=2, R=3. Then total sum modulo 3. But I don’t know.

Alternatively, the problem is similar to a system where the final color depends on the total number of eggs modulo 3. For example, if the total number of eggs after adding is 100, which is 1 mod3. Then, the final color would be the color corresponding to 1. But I need to check the combination rules.

If each fusion effectively subtracts 1 from two colors and adds 1 to the third, then the total number modulo 3 remains the same. For example, starting with total T ≡ sum(B,P,R) mod3. Each fusion subtracts 2 and adds 1, net change -1 ≡ 2 mod3. But since each fusion reduces the total by 1, the total modulo3 decreases by 1 each time. Starting from 100 ≡1 mod3, after 99 fusions (subtracting 99 ≡0 mod3), the final total is 1 ≡1 mod3. Not sure how this helps.

Alternatively, considering that the combination rules cycle through colors, the final color might depend on the initial sum modulo 3. If the total number of eggs after adding is congruent to 1 mod3, and the combination rules cycle every 3 steps, then the final color would be blue (0), purple (1), red (2) based on the initial sum. But I need to check.

In case 1: total 100 ≡1 mod3. Final color blue (0). 1 mod3 corresponds to blue? Not sure. Case 2: total 100 ≡1 mod3, final color purple (1). Case 3: total 100 ≡1 mod3, final color blue (0). So inconsistency.

This suggests that the modulo3 approach isn’t directly applicable. Therefore, my earlier simulations are more reliable.

According to the simulations, adding blue or red leads to blue final egg. However, the problem might expect only one answer. This could be due to a mistake in the problem’s numbers, which originally summed to 99 instead of 39. If the initial total is supposed to be 39, but the counts are different, the answer would change. However, given the provided numbers, both adding blue and red work. But since the problem allows adding exactly one egg, and the answer requires choosing one, perhaps there’s a mistake in the simulation.

Alternatively, maybe when adding red, the final color is not blue. Let me recheck case 3.

Case 3: adding red → B=23, P=33, R=44.

Fuse R and P 33 times → R=11, P=0, B=56.

Fuse B and R 11 times → B=45, R=0, P=11.

Fuse B and P 11 times → B=34, P=0, R=11.

Fuse B and R 11 times → B=23, R=0, P=11.

Fuse B and P 11 times → B=12, P=0, R=11.

Fuse B and R 11 times → B=1, R=0, P=11.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=10, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=9, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=8, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=7, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=6, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=5, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=4, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=3, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=2, B=0, R=1.

Fuse P and R 1 time → P=1, R=0, B=1.

Fuse P and B 1 time → P=0, B=0, R=1+1=2?

Wait, no. Wait, when you fuse P and B, each fusion reduces P and B by 1, increases R by 1. So fusing P=1 and B=1:

P=0, B=0, R=1+1=2. But wait, according to the combination rules, P and B fuse to R. So each fusion takes one P and one B, makes one R. So starting with P=1, B=1:

After fusion: P=0, B=0, R=2. Now, you have two R. Then, you need to fuse them. But the rules don’t allow fusing two R. So this contradicts the problem’s requirement to fuse until one remains. Therefore, this suggests that the simulation is incorrect because when you have two R eggs, you can’t fuse them (as per the given rules), leading to a contradiction.

Ah, this is the critical mistake. In my previous simulations, I assumed that when only two eggs of the same color are left, you can fuse them, but the problem’s rules only allow fusing different colors. Therefore, when we reach a point where we have two R eggs, we can’t fuse them, and the problem cannot proceed. This indicates an error in my earlier approach.

Therefore, the correct way to simulate is to never fuse two eggs of the same color. So when you reach a state where only one color remains, you stop. However, according to the problem, you must fuse until one egg is left. This implies that the initial counts must be such that you never end up with two eggs of the same color at the end. Therefore, the fusion process must be designed to avoid this.

This changes everything. Let’s re-express the simulation with this in mind.

Revisiting case 3:

After adding red, we have B=23, P=33, R=44.

Fuse R and P 33 times: R=11, P=0, B=56.

Now, B=56, R=11. Fuse B and R 11 times: B=45, R=0, P=11.

Now, B=45, P=11. Fuse B and P 11 times: B=34, P=0, R=11.

Now, B=34, R=11. Fuse B and R 11 times: B=23, R=0, P=11.

Now, B=23, P=11. Fuse B and P 11 times: B=12, P=0, R=11.

Now, B=12, R=11. Fuse B and R 11 times: B=1, R=0, P=11.

Now, B=1, P=11. Fuse B and P 1 time: B=0, P=10, R=1.

Now, P=10, R=1. Fuse P and R 1 time: P=9, R=0, B=1.

Now, P=9, B=1. Fuse P and B 1 time: P=8, B=0, R=1.

Now, P=8, R=1. Fuse P and R 1 time: P=7, R=0, B=1.

… Continuing this until:

P=2, B=1. Fuse P and B: P=1, B=0, R=1.

Now, P=1, R=1. Fuse P and R: P=0, R=0, B=1. Final egg is blue.

But according to the rules, fusing P and R when they are both 1 is allowed, resulting in B. So this is correct. The key is that as long as there are two different colors, you can fuse them. When only two eggs of different colors are left, you fuse them into the third color. Therefore, the simulation is correct, and adding red does result in blue.

However, in case 2, adding purple leads to P=3 at the end, which would require fusing two P’s, but that’s not allowed. Wait, no: in case 2, after adding purple, we ended up with P=3. How does that happen?

Let me recheck case 2:

Case 2: adding purple → B=23, P=34, R=43.

Fuse R and P 34 times: R=9, P=0, B=57.

Fuse B and R 9 times: B=48, R=0, P=9.

Fuse B and P 9 times: B=39, P=0, R=9.

Fuse B and R 9 times: B=30, R=0, P=9.

Fuse B and P 9 times: B=21, P=0, R=9.

Fuse B and R 9 times: B=12, R=0, P=9.

Fuse B and P 9 times: B=3, P=0, R=9.

Fuse B and R 3 times: B=0, R=6, P=3.

Now, R=6, P=3. Fuse R and P 3 times: R=3, P=0, B=3.

Now, R=3, B=3. Fuse R and B 3 times: R=0, B=0, P=3.

Now, P=3. But we need to fuse until one egg is left. With P=3, how?

Fuse two P’s → not allowed by the rules. Therefore, this is impossible. This means that adding purple leads to an impossible situation where you can’t fuse anymore, contradicting the problem’s requirement. This suggests a mistake in the problem’s initial conditions or a misinterpretation.

However, according to the problem statement, you must fuse until one egg is left. Therefore, the process must be designed to avoid such a situation. This implies that the counts after each step must always allow fusing different colors until one remains. Therefore, my previous simulations have an error.

This means that when we reach a state with only one color left, but more than one egg, we cannot proceed. Hence, such a case is invalid, and the only valid cases are those that end up with exactly one egg through proper fusions.

Therefore, in case 2, when we reach P=3, we can’t fuse, so this path is invalid. Hence, adding purple would result in an invalid state, implying that the problem has no solution when adding purple. However, according to the problem, there must be a solution.

This suggests that there’s a mistake in the simulation. Let me re-express case 2:

Case 2: adding purple → B=23, P=34, R=43.

Fuse R and P 34 times: R=43-34=9, P=0, B=23+34=57.

Now, B=57, R=9. Fuse B and R 9 times: B=48, R=0, P=9.

Now, B=48, P=9. Fuse B and P 9 times: B=39, P=0, R=9.

Now, B=39, R=9. Fuse B and R 9 times: B=30, R=0, P=9.

Now, B=30, P=9. Fuse B and P 9 times: B=21, P=0, R=9.

Now, B=21, R=9. Fuse B and R 9 times: B=12, R=0, P=9.

Now, B=12, P=9. Fuse B and P 9 times: B=3, P=0, R=9.

Now, B=3, R=9. Fuse B and R 3 times: B=0, R=6, P=3.

Now, R=6, P=3. Fuse R and P 3 times: R=3, P=0, B=3.

Now, R=3, B=3. Fuse R and B 3 times: R=0, B=0, P=3.

Now, P=3. We can’t fuse further, which is invalid. Hence, this case is impossible, meaning that adding purple is not a valid solution.

Therefore, only adding blue or red work. But according to the problem, the answer should be adding a blue egg. However, my simulation shows both blue and red work. But perhaps there’s a mistake in case 3.

Rechecking case 3:

After adding red, the simulation ends with blue. But let’s check the step where we have P=1, R=1.

Fuse them → B=1. Correct.

But in case 3, the final steps are valid because you can always fuse different colors. Therefore, case 3 is valid.

However, the problem states that you can add exactly one egg. If both blue and red work, then the answer would be either. But since the problem likely expects one answer, there must be a mistake.

Upon reviewing, the initial counts sum to 99 eggs, but the problem says 39. This inconsistency suggests that the correct counts might be different. For example, if the total is 39, the counts might be 23 blue, 13 purple, 3 red (23+13+3=39). If that’s the case, the simulation would be different. However, the user provided the counts as 23 blue, 33 purple, 43 red, totaling 99. Given this inconsistency, it’s possible that the intended counts were 2 blue, 3 purple, 34 red (sum 39), but without the correct numbers, it’s impossible to be certain.

Assuming the problem’s counts are correct as given (sum 99), then the answer is to add either blue or red. However, since the problem requires a single answer, and given that both simulations work, there might be a mistake. Alternatively, the intended answer is to add a blue egg. However, without more information, I’ll proceed with the simulations as per the given numbers.

Response

To determine which egg to add for the final egg to be blue, we analyze each scenario:

- Adding a Blue Egg (Total: 100 eggs)

- Fuse Red (43) and Purple (33) → creates Blue. Continue until Purple depletes.

- Remaining eggs: Blue (57) and Red (10). Fuse to create Purple.

- Continue alternating fusions between the two largest piles, eventually leading to a final Blueegg.

- Adding a Purple Egg (Total: 100 eggs)

- Fuse Red (43) and Purple (34) → creates Blue. Continue until Purple depletes.

- Ends with an invalid state where only Purple eggs remain, unable to fuse further. Final egg: Purple.

- Adding a Red Egg (Total: 100 eggs)

- Fuse Red (44) and Purple (33) → creates Blue. Continue until Purple depletes.

- Alternate fusions between remaining piles, leading to a final Blue egg.

Conclusion: Adding either a blue or red egg results in a blue final egg. However, due to potential typos in the problem’s egg counts, the intended answer is likely blue.

Answer: Add one blue egg. \boxed{blue}